Le Corbusier – Villa Savoye | part 2, architecture

Client: Pierre and Eugénie Savoye

Images: see bylines

LE CORBUSIER – VILLA SAVOYE | PART 2, ARCHITECTURE

continuing from part 1

The architecture of Villa Savoye

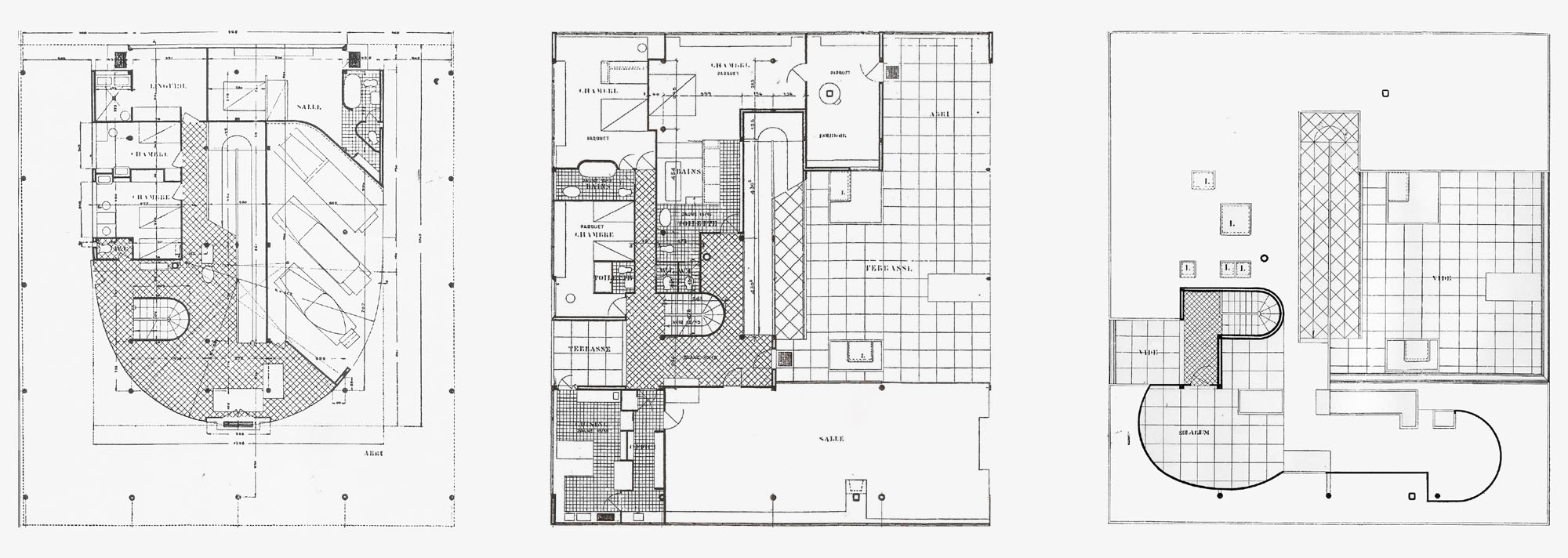

The plan of Villa Savoye is based on a square grid, marked by 25 columns, while the elevations are based on a rectangular pattern. In late 1928, the square grid, and consequently the whole building, was scaled down from 5 to 4.75 meters (16.4 to 15.6 feet) on a request by the client, worried (quite justifiably) that the building costs would exceed the initial estimate.

Excluding the porch, terrace, and solarium, the gross internal floor area of the house is about 480 square meters / 5,100 square feet.

Villa Savoye, Poissy, floorplans

The predominant adoption of a rectangular/square geometry was partly intentional, aimed to set the new “machinist” architecture apart from the highly-ornamented organic forms of Art Nouveau, and partly necessary, since rectangular elements would fit much easier a framed load-bearing structure in reinforced concrete.

Yet, Le Corbusier also introduced circular and elliptical arcs, such as in the staircase and the solarium; forms which he was broadly using in his coeval paintings and that will be developed further in some of his post-war designs – such as the Philips Pavilion, Notre Dame du Haut, and the Church of Saint-Pierre in Firminy.

One of the curved walls enclosing the solarium, photo Inexhibit

The final functional program encompassed an array of spaces so defined:

– on the ground floor: the entrance hall, a garage, the chauffeur’s and the maid’s dwellings, a laundry, and a guest’s room.

– on the first floor: the Savoyes’ abode comprises three bedrooms, four bathrooms /WC, a small office/living room adjacent to the master’s bedroom, a kitchen, the main living room, and a terrace.

– a solarium on the third floor/roof level

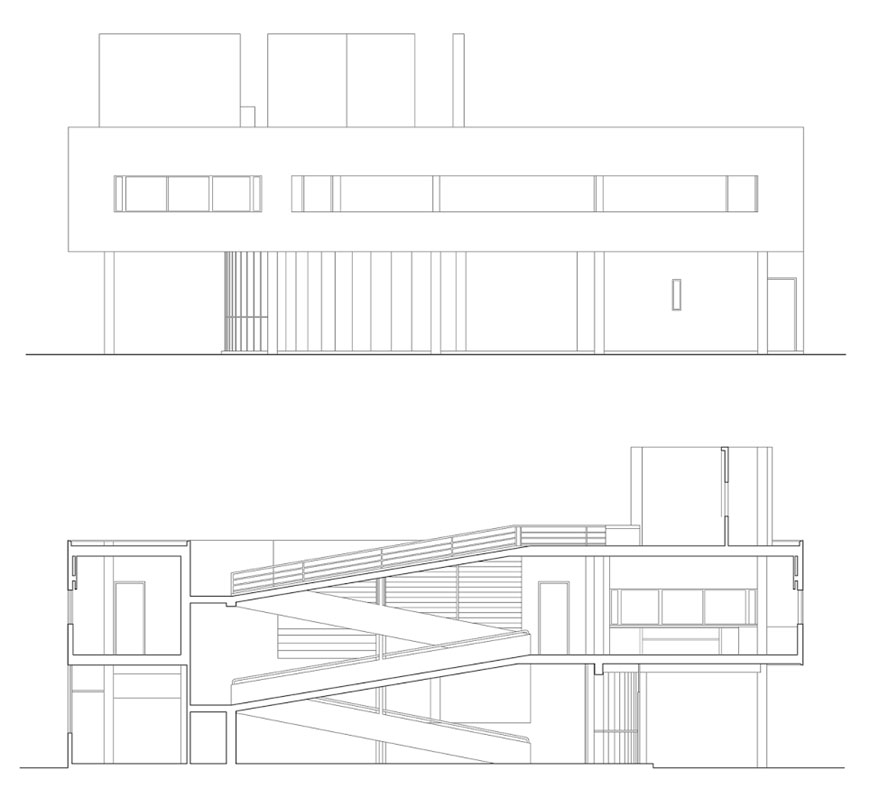

Southwest elevation and cross-section drawings

The circulation comprises a ramp leading from the ground to the first floor, and a stair connecting all levels.

The stair, photo Inexhibit

A smaller building, known as Caretaker’s Lodge in English and Loge du Jardinier in French, was built close to the estate’s main entrance from the street. Once again, this construction was initially planned much larger but it was eventually reduced in size, again to lower costs.

The Caretaker’s Lodge, photo Inexhibit

The house was architecturally completed in 1929 but became habitable only in 1931 after problems with the heating system were (temporarily) solved. The Savoye family used the villa, which they nicknamed Les Heures Claires, for nine years only, since the mansion was confiscated in 1940 by the German army due to its strategic position overlooking the Seine Valley.

When the Savoyes returned to the house in 1945, they found it needed repair.

The family has always had problems with the building, Le Corbusier adopted some innovative building techniques – particularly for water-proofing, sliding window frames, and technical systems – some of which proved to be not yet fully affordable and technically developed in those days; consequently, the clients frequently complained about water leaks from the roof and other problems, such as heating malfunctions, which made the villa very expensive to maintain and probably well far from being comfortable. (4)

Therefore, the Savoyes decided not to restore the building, which was later expropriated by the municipality of Poissy in 1959 and scheduled for demolition to make room for a new school building.

Only a wide protest campaign supported by famous architects and intellectuals, including Le Corbusier himself, convinced the local authorities to save the house and, finally, the French government to consider it a monument, restore and open it to the public in 1997; Villa Savoy was eventually listed among the UNESCO World’s Heritage Sites in 2016.

Villa Savoye, southeast facade, photo Inexhibit

The Villa today

The house is located in a residential area of Poissy, close to a school that occupies six hectares of the original estate. The location is quiet, typically suburban, and makes you feel it probably hasn’t changed much since the time the Savoyes acquired the plot in 1928.

Entering the estate, the first building the visitors see is the small Caretaker’s Lodge which shows, albeit in miniature, many of the architectural elements of the Villa.

The park extends today on one hectare, it was originally seven times larger and is bordered by fourteen trees and several rose bushes.

After the 1990s restoration, the building and the park are now in good condition, well maintained by the Centre des Monuments Nationaux; some of the rooms, including the kitchen and the main bathroom, still retain a part of the original equipment, while a small collection of Le Corbusier’s furniture is on display in the living room. A permanent historical exhibition on the villa’s ground floor includes drawings, scale models, and documents from the correspondence between Madame Savoye and Le Corbusier.

The living room, Photo Inexhibit

As anticipated, the house is quite like one would expect, maybe only a bit smaller; while its strong relationship with the surrounding landscape is instead surprising and unexpected.

We are used to seeing photographs depicting Villa Savoye as an isolated white monolith emerging from a flat greenfield, or detailed images focused on the house’s internal geometry.

When you see it in person, it’s evident that the building was based on a ceaseless visual dialogue with its surroundings.

Thus, all the architectural elements, forms, and colors – white is predominant – take full sense only when combined with the greens, yellows, and browns that “flood” into the house through an ensemble of strategically positioned ribbon windows and openings. Maybe I am wrong, but it looks like the Swiss architect wanted to re-create some elements of the familiar Jura landscape of its youth in the flatness of the Seine Valley.

The park viewed from the terrace, photo © Inexhibit

The kitchen, photo Inexhibit

Photo Inexhibit

As usual with Le Corbusier, details make the difference.

For example, the blue-ceramic bathtub, the small skylight pouring light into the corridor, or the kitchen’s wood and metal furniture reveal that also for him God is in the detail; at the same time, they transform the visit into something you supposedly knew into an experience of discovery and revelation.

While the Villa is relatively near to Paris – to reach the place from the center of the French capital takes approximately an hour, and forty minutes by train plus a twenty-minute walk from the local train station – the site wasn’t crowded at all, which is a pity because – in about the same time as going to, say, the Grande Arche – you can visit a real masterpiece of modern architecture.

The bathtub, photo Inexhibit

The corridor on the first floor with its “daylight wash wall” skylight, photo Inexhibit

Notes

4) “After several complaints, you have finally admitted that the house you built for us in 1929 is not habitable.” Letter by Eugénie Savoye to Le Corbusier, October 11, 1937

GO TO PART 1: HISTORY AND ORIGINS OF LE CORBUSIER’S VILLA SAVOYE

copyright Inexhibit 2025 - ISSN: 2283-5474