Olivetti Programma 101: at the origins of the Personal Computer

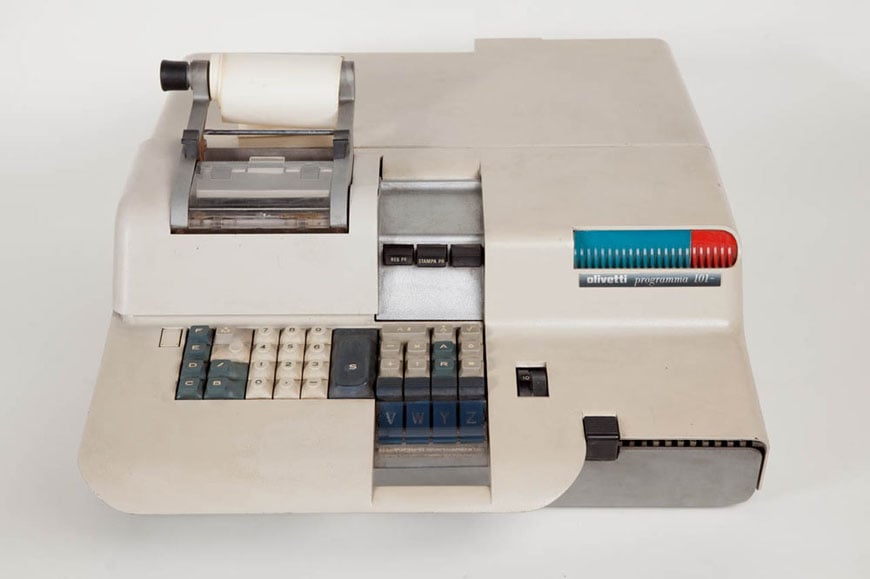

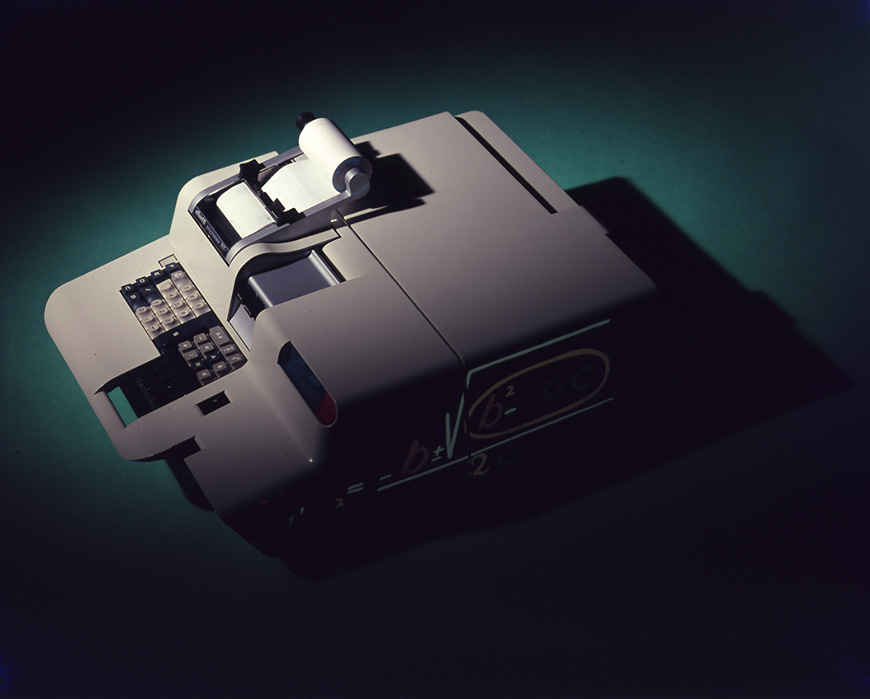

An Olivetti Programma 101, photo courtesy of Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia “Leonardo da Vinci”, Milan (CC BY-SA 4.0).

At the origins of the Personal Computer: the Olivetti Programma 101 (1965)

These days, Italy is not particularly renowned for its consumer electronics products; yet, there was a time, in the ’60s, when an Italian company was reputed to be the “European response” to American computer manufacturers; that company was Olivetti.

The company was founded in Ivrea, Northern Italy, in the early 20th century as a typewriter maker; but, in the late ’50s, under the direction of Adriano Olivetti and his son Roberto, it became one of the first European companies to regularly produce electronic calculators and computers, often characterized by innovative design and engineering solutions.

The first human-centered computer

It was in the early Sixties that Olivetti decided to develop a “desktop” computer; namely, a computer much smaller than those used at the time, and compact enough to be “a personal object, something that had to live with a person, a person with his chair sitting at a table or desktop” (Roberto Olivetti). This object was the Programma 101.

This idea was utterly revolutionary since, at the time, computers were massive mainframes sealed in airtight rooms and operated by an elite of specialized technicians in white coats. Just before revealing the “dream machine”, a Programma 101 advertisement recited: “Welcome to the world of tomorrow. You are about to take a journey out of this world into the world of the future”, another one was showing a businessman and a handsome woman in a swimsuit (his secretary, perhaps) working on a Perottina right at the side of a pool…

A 1960s video advertisement of the Olivetti P101 for the U.S. market.

The development stage

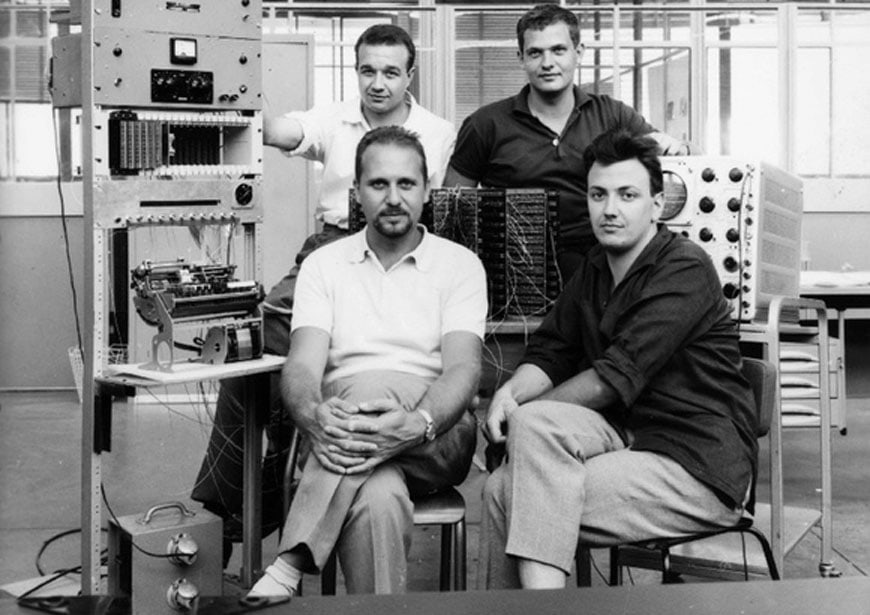

The Programma 101 takes its nickname, Perottina, from that of its inventor – Italian electrical engineer Pier Giorgio Perotto, then 32 years old – to whom Olivetti assigned the direction of the project in 1962. The computer was developed by an engineering team of five young technicians which included – along with Perotto – Giovanni De Sandre, Giuliano Gaiti, Gastone Garziera, and Giancarlo Toppi.

The early story of the Programma is somewhat romantic. Olivetti had just sold its electronics division to General Electric, which wasn’t interested in an “Italian computer” at all.

Yet, the team didn’t want to give up the project, already in an embryonic stage; therefore, they invented a trick. Overnight, they warily declassified the machine from “computer” to “calculator”, and the calculator division was not part of the agreement with GE. So they could go on developing for some crucial months their “machine of the future”, in a sort of no man’s land between Olivetti and General Electric.

The technical development team of Programma 101 (except Giuliano Gaiti); left to right and bottom to top: Pier Giorgio Perotto, Giovanni De Sandre, Gastone Garziera, and Giancarlo Toppi; photo courtesy of Laboratorio-museo Tecnologicamente, Ivrea / Wikimedia.

When we look at the specifications and capabilities of the machine, today, it is hard to think it was a real computer.

Due to its limited RAM of 1,920 bits, the Programma 101 was mostly a machine conceived to make arithmetic calculations – sums, subtractions, divisions, multiplications, square roots -, yet, like modern computers, it could also perform logical operations, conditional and unconditional jumps, and print the data stored in a register, all through a custom-made alphanumeric programming language. This was, in the early ’60s, what set computers apart from calculators, indeed.

Overall, in today’s terms, Programma 101 can be considered a sort of “transitional fossil” between desktop calculators and personal computers.

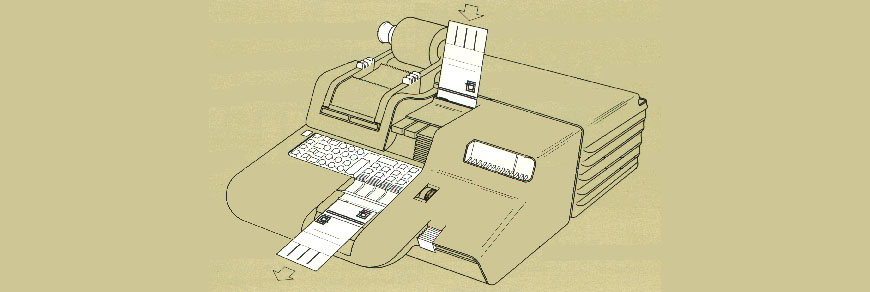

The P101 didn’t have a monitor or the like, it used a small paper tape printer as a visualization device, instead. A revolutionary innovation made by Olivetti was to replace the fridge-size magnetic tape mass memory devices typical of coeval mainframes with a programmable magnetic card reader/recorder.

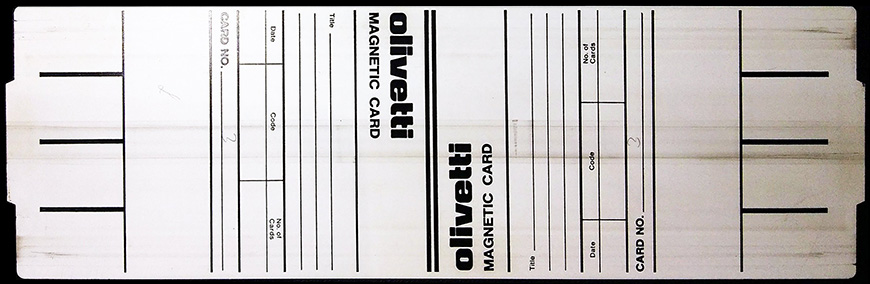

Programs were recorded on these plastic strips, about 3 inches wide and one foot long, which could contain only 240 instructions and were very slow but were also small, simple to use, and quite practical overall. The magnetic bands were on one side of the card, so the other could be used to write annotations and the names of the programs they contained.

An image showing how the memory cards were used and a photo of one of the original magnetic cards; images courtesy of Computer Museum / University of Amsterdam and Bech (CC BY-SA 4.0) / Inexhibit.

The machine didn’t have a microprocessor or integrated circuits; like most computers of the time, its electronics were exclusively based on transistors, diodes, capacitors, and the like, grouped into larger functional “micro-units” (a patented technology specially developed by Olivetti for the Programma 101).

The interior of the P101 “Perottina”; photo ICTP Scientific FabLab; the front-right section accommodates the power supply and the electric motor; the front-middle-to-left section contains the keyboard, the printer, and the card reader/recorder; the rear section is reserved for the electronic section, cooled by a fan.

The design of the Programma 101 body

The design of the Programma’s body was conducted by Mario Bellini, a then-young architect, who was preferred to other designers who had previously worked for Olivetti, such as Ettore Sottsass, Marco Zanuso, and Marcello Nizzoli. Zanuso was contacted at first, but his proposal was a massive self-standing box, similar to that of a mainframe, which would have nullified all the effort to keep the device as small and lightweight as possible.

The team of Perotto had already created an impromptu wood case for the machine, just to give the P101 some kind of a container, but they were aware they still needed an open-mind architect keen to work on something never seen before. The young Bellini was possibly that man.

For the P101, Bellini conceived a case, mostly made in cast aluminum, whose round-edge shape set it apart from other electronics products by Olivetti, such as the mainframe ELEA 9003 designed by Sottsass only a few years before.

The decision to make the case of Programma 101 in an unconventional material such as die-cast alloy (most computers of the time were made in sheet metal) was justified by the need to avoid electromagnetic interference in a home/office environment.

The case was 3 mm. thick and relatively lightweight (the whole machine weighed about 65 lbs. / 30 Kg. ).

Bellini would have probably designed it to be made in plastic if synthetic materials were sufficiently developed at the time, which wasn’t the case. For example, in 1964, Ettore Sottsass designed a lined housing for the Olivetti Praxis 48 typewriter also to conceal the imperfections and the visually unpleasing shininess in its plastic die.

The case of the Olivetti Praxis 48 typewriter was designed in 1964 with a lined texture to disguise the imperfection of its innovative plastic body; image Charles Kremenak (CC BY 2.0).

The sharp-edged, angular forms of the mainframe Olivetti ELEA 9003 were typical of the late ’50s and early ’60s computers; image Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia “Leonardo da Vinci” (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The design of the Perottina is somewhat reminiscent of that (again by Sottsass) of the Olivetti Logos 27 electromechanical calculator, which was first presented, together with the Programma 101, in October 1965 at the Bema (Business Equipment Manufacturer Association) show in New York. Like the 101, the Logos 27 also had a die-cast alloy case; overall, both machines look a bit like big typewriters.

Nevertheless, the case of the Programma is much more futuristic, bright, and “friendly” than the rather serious one of the Logos.

The electro-mechanic calculator Olivetti Logos 27 (1965), design: Ettore Sottsass; photo Piergiovanna (CC BY-SA 4.0) / Inexhibit.

Desk-top computer Olivetti Programma 101 (1965); design: Mario Bellini; photo courtesy of Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia, Milan (CC BY-SA 4.0).

I see in it some elements – such as the use of thin lines to make the object appear smaller than it actually was, the playful contrast between the almost-white color case and the vividly-colored logo area, and the uncluttered design of slots and handles – which recall me the “Snow White” design language developed for Apple by German designer Hartmut Esslinger twenty years later.

Photo courtesy of Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia, Milan (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Photo by Paolo Monti / BEIC Digital Library (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Photo by ☰☵ Michele M. F. / Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The P101 commercial success and legacy

Despite Olivetti initially having modest expectations of the commercial possibilities of Programma 101, the computer was a success.

With a price of $3,200 (about 20,000 in today’s dollars), it was quite cheap if compared to other computers of the time, which were mostly expensive mainframes reserved for big companies, government agencies, and universities. Furthermore, the Perottina was small and you could easily move it from one room to another, plug it into a power socket, and start working in minutes.

In his book on the story of the P101, Perotto reports that some visitors of the Bema Show, when the machine was presented for the first time, believed that it was a sham, and was some sort of a console attached to a mainframe secretly concealed somewhere else.

Olivetti sold about 44,000 Programma 101 units, mostly in the United States, including 10 machines that NASA used for the Apollo 11 program.

“By Apollo 11 we had a desktop computer, sort of, kind of, called an Olivetti Programma 101. It was kind of a super calculator. (…) It would add, subtract, multiply, and divide, but it would remember a sequence of these things, and it would record that sequence on a magnetic card (…). So you could write a sequence, a programming sequence, and load it in there” David W. Whittle, Johnson Space Center, NASA

What makes the Perottina a quantum leap in computer concept and design was being the first human-centered computer ever made.

The company’s leaders and designers shared the same objective: to create for the first time a computer aimed at common people, not technicians and scientists only.

And to achieve that they had to focus on the relationship between humans and machines, besides the pure computational performances of the computer.

“Those days, few manufacturers and designers were interested in the user’s perspective and user-friendliness of machines. After all, In the ’60s, the available technology was limited, and the interest of computer designers was entirely focused on technical issues and on making devices work. It was the user who had to adapt to the machine, not the opposite. The electronics had to provide quantitative performances – as much computational power, memory, and printing speed as possible -, there was no room to improve the relationship between computers and their users who, moreover, were all specialized technicians. Despite technology was improving in power, nevertheless, it didn’t leave much to those interested in making machines more friendly and easy to use.” (Pier Giorgio Perotto, Programma 101. The never told, fascinating story of the invention of the Personal Computer, p. 20)

That’s why the Programma was technically and aesthetically conceived as an unintimidating object everyone could use, even at home. In that sense, there is no doubt that the Olivetti Programma 101 truly is the first Personal Computer in history.

Furthermore, if industrial design is a discipline aimed at creating relationships between useful objects and their users, the Perottina can be considered possibly the first computer to have been designed.

Photo by Emanuele / Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

References

For images and technical info on the Programma 101 see:

The incredible story of the first PC, from 1965 (http://royal.pingdom.com/2012/08/28/the-first-pc-from-1965/, in English)

Olivetti Programma 1010 (http://www.silab.it/frox/p101/_index.html , in English)

PROGRAMMA 101 – Memory of the Future by Alessandro Bernard and Paolo Ceretto (http://www.101project.eu/the-documentary/, video)

“Alle origini del personal computer: l’Olivetti Programma 101” (http://www.storiaolivetti.it/percorso.asp?idPercorso=630, in Italian)

La Programma 101, il primo personal computer al mondo (http://www.piergiorgioperotto.it/programma101.aspx, in Italian)

copyright Inexhibit 2025 - ISSN: 2283-5474