The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, an American revolution

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Restoration Completion. Photograph by David Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

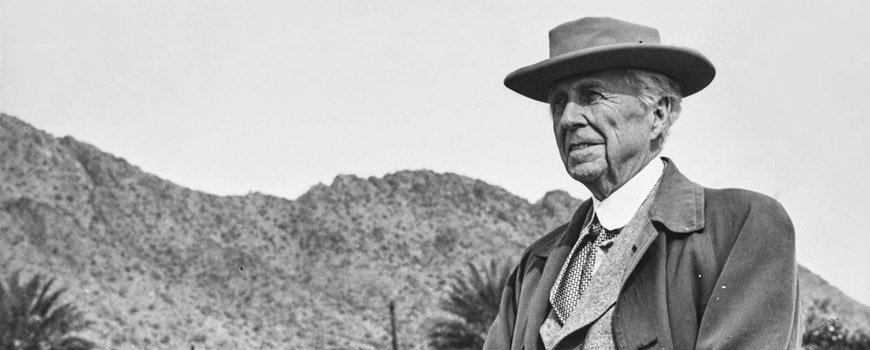

“I need a fighter, a lover of space, an originator, a tester and a wise man”

(From the June 1943 letter by Hilla von Rebay to Frank Lloyd Wright)

THE GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, AN AMERICAN REVOLUTION

by Riccardo Bianchini, Inexhibit

Introduction

The oldest public museums opened in Italy during the Renaissance. The Capitoline Museum and the Vatican Museums are perhaps the first institutions that we could call “museums”, although they were not open to all, while the Ashmolean in Oxford, UK is the true archetype of a modern museum and the first housed in a building specifically conceived for that purpose.

The configuration of museum buildings remained substantially unchanged for almost three centuries: a fixed sequence of rooms where paintings were hung on the perimeter walls and large sculptures were placed directly on the pavement, sometimes supported by a pedestal. Visitors were supposed to view the artworks by following a linear logic, sometimes chronologically sometimes thematically, to appreciate them fully one by one.

This concept is still very common today and was ubiquitous in 1943, when Hilla von Rebay, the art advisor to Solomon R. Guggenheim, sent a letter to Frank Lloyd Wright asking him to design a new building for Guggenheim’s Non-Objective Painting collection.

The desire of the client was to create a natural and organic relationship between artworks and architecture: “…each of these great masterpieces should be organized into space” since “(these paintings) are order, creating order and are “sensitive” (and correcting even) to space”, Hilla Rebay wrote in her commission letter to Wright.

Top and bottom, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Restoration Completion, Photograph by David Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

The Guggenheim during construction in 1957, photo by Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (Public Domain).

The birth of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The challenge that Wright faced required a completely new approach to museum architecture and exhibition design. The first problem was to find a suitable plot of land, it is known that Wright did not approve of New York, a city that he viewed as “overbuilt and overpopulated” and lacking the close relationship with nature that was the hallmark of his architectural vision. The only place that Wright found sufficiently inspiring faced Central Park, a natural idyll in the center of Manhattan’s dense urban agglomeration. To achieve the necessary union between exposed art and architecture, Wright decided to adopt a continuous, organic shape with a large central void encircled by a long uninterrupted exhibition path in the form of a descending ramp. The inspiration was most likely a previous design by Wright for the unrealized Gordon Strong Automobile Objective, a panoramic overlook on Sugarloaf Mountain that visitors would reach by driving their cars along a giant spiral ramp.

The gestation of the project was not a simple one; Wright prepared four proposed versions of the building, three with a circular shape and one with a hexagonal one, but it was not clear whether the building should have a horizontal or a tall appearance, or even if it had to be vigorously colored or monochrome. Furthermore, the relationship between the architect and the client, and particularly with Hilla Rebay, was often difficult. Although a project, similar to what was finally built, was substantially defined in September 1945, nevertheless it took 14 more years to see the building completed, mainly because of planning consent problems and a troubled relationship between Wright and James Sweeney, the new museum director who replaced Rebay in 1952. In the meantime, both Solomon R. Guggenheim, in 1949, and Wright, six months before the museum’s opening in October 1959, had died.

Neither one saw the building completed.

A September 1943 ink drawing by Wright of the Guggenheim project showing one of the red-colored versions. © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona

A revolutionary exhibition space

The exhibition space conceived by Wright was revolutionary: a whole, enveloping volume where visitors at first reach the top level by elevator, then gently descend on a ramp while admiring the paintings arranged along the way. Every 30 degrees, a narrow load-bearing wall gives a precise cadence to the path. The space is unified, there are no traditional exhibition halls or secluded treasure rooms, almost all parts of the museum can be perceived from every point inside it and the visitors always know where they are and where they are going. From the central lobby (the “Rotunda”) several exhibition levels can be seen simultaneously.

Top: An original sketch by F.L. Wright of the Guggenheim interior. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation – Scottsdale – Arizona

Bottom: Installation view of RUSSIA!, 2005. Photo: David M. Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

This revolutionary concept also had its drawbacks: there are almost no horizontal floors, with the exception of the rotunda which Wright intended as a social and gathering space, not for exhibition purposes. There are few planar walls on which paintings could be hung and the reduced ceiling height inside the exhibition ramp makes it unsuitable for displaying large artworks. Paintings usually must be affixed to the inclined perimeter walls with special steel rods (although Wright envisaged that they should be mounted following the wall inclination).

Furthermore, many artists felt that their works were overpowered by the architectural strength of the “container” and worried that their artworks would not receive the necessary “sympathetic” attention from the visitors. In a 1956 letter to Sweeney, 32 artists, including De Kooning and Motherwell, also say: “The basic concept of curvilinear slope for presentation of painting and sculpture indicated a callous disregard for the fundamental rectilinear frame of reference necessary for the adequate visual contemplation of works of art”.

Wright’s gesture required a completely new approach to art museography.

One interesting example is related to sculpture display. Since the whole exhibition space is sloped and the surrounding walls are not vertical, it is arguable that sculptures could be exhibited either by following the ramp inclination or by keeping them in a perfectly vertical position using a special pedestal or a small platform. It turned out that the peculiar geometry of the building produced an optical illusion making a perfectly vertical sculpture look unpleasantly tilted. It was up to Thomas M. Messer, the Guggenheim director at that time, to find a solution: a support inclined at a specific angle so that the sculpture seemed vertical even if it actually was not.

Top: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Installation view of The Aztec Empire, 2004.

Photo: David M. Heald, © SRGF, New York.

Bottom: Installation view: Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21–September 1, 2014. Photo: Kris McKay, ©SRGF

In 1992, a museum extension designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects was realized, following Wright’s original project; an eight-story rectangular tower just behind the main building was added, providing a series of more traditional flat-floor exhibition rooms that eventually allowed large paintings and sculptures to be exhibited more practically.

Top: The new addition tower is visible in the background on the left. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Restoration Completion, Photograph by David Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Bottom: one of the exhibition rooms that were added in 1992. Installation view: Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21–September 1, 2014. Photo: Kris McKay, ©SRGF.

Lighting the museum

Natural lighting was a key point in Wright’s design: a large domed skylight provides a diffuse background illumination to the internal space while a continuous band of ribbon windows supplies a specific natural illumination for the artworks located along the exhibition ramp.

The reason for such attention to natural light also originated from Wright’s dislike for artificial lighting, which he deemed “dishonest” as stated in a 1955 letter he wrote to Sweeney: “A humanist must believe that any picture in a fixed light is only a “fixed” picture! If this fixation be ideal then see death as the ideal state for men. The morgue”. Nevertheless, an artificial lighting system was eventually added to ensure proper illumination of artworks under all conditions.

Top: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Installation view of Picasso and the Age of Iron, 1993.

Photo: David M. Heald, © SRGF, New York.

Bottom: Installation view: Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21–September 1, 2014. Photo: Kris McKay, ©SRGF.

The Wright’s Guggenheim Museum legacy

One interesting question is whether or not Wright’s design has become a model. Few museums present a ramped exhibition space; many of them are automobile museums (such as the BMW Museum by UN Studio and the Mercedes-Benz Museum by Atelier Brückner in Germany, and in part the Enzo Ferrari Museum in Modena by Future Systems). These evoke the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective that was perhaps a starting point for Wright when approaching the design of the Guggenheim. Some others, such as the Macba in Barcelona, the Denver Museum by Libeskind, the Hanoi Museum, and the Hellenic Museum in Athens, present large iconic ramps, albeit they are rarely used as actual exhibition spaces. Possibly, the museum that more closely matches the exhibition concept of the Guggenheim has also the most different gestation imaginable: the Museum of Cinema in Turin, housed in a monumental domed building designed as a synagogue in the 19th century by Alessandro Antonelli, to which a long temporary exhibition spiraling ramp was added in 2000.

Left: the Mercedes-Benz museum in Stuttgart, photo Brigida González © Mercedes‑Benz Group AG. Right: the BMW Museum in Munich, courtesy of BMW AG.

One element of the Guggenheim design that has become an archetype for many exhibition buildings, particularly in recent times, is the principle of a museum as a whole space, uninterrupted and interconnected, where all parts overlook one another, usually through a large central void.

Perhaps this aspect of Wright’s and Guggenheim’s revolutionary museum vision has been most widely accepted. Modern museums are increasingly conceived as less “sacred” institutions, used for socializing and education, where culture can be disseminated to a large, diverse public and where exhibited objects and artworks contribute to a manifold and complex perceptive experience.

Left: The Museum of Cinema in Turin © Inexhibit. Right: The central hall of the MUSE museum in Trento by Renzo Piano Building workshop. © Inexhibit.

copyright Inexhibit 2025 - ISSN: 2283-5474