Le Corbusier, Unité d’Habitation – Cité Radieuse, Marseille

Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France

One of the most famous architectural projects by Le Corbusier and a UNESCO world heritage site, the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, also known as Cité Radieuse, is a 1952 residential building partially open to the public.

Above, the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille by Le Corbusier, east facade; photo Wojtek Gurak (CC BY-NC 2.0) via Flickr.

History

Designed by Le Corbusier with Portuguese architect and artist Nadir Afonso in the 1940s, the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille was the first of five similar buildings realized in France and Germany between 1952 and 1965.

The design of the Unité building in Marseille was commissioned to Le Corbusier by the French Government (represented by the Minister of Reconstruction, M. Raoul Dautry) shortly after the end of World War Two to create a model for a new generation of public housing complexes to be built throughout France.

To cope with the project’s strict technical and financial constraints, Le Corbusier devised a single large building that could accommodate up to 1,600 people. In the same period, the Swiss architect also designed two larger housing complexes for 20,000 people – one for La Rochelle, in the Charente-Maritime department, and the other for St-Dié, in the Vosges department – each consisting of eight “Unité” buildings similar to that in Marseille, none of which were realized. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, four single “Unité d’Habitation” were built In Nantes, Briey, Firminy, and Berlin between 1955 and 1965.

While the design of the Unité is rooted in various of le Corbusier’s experimental projects of the 1920s and 1930s, such as his Immeubles Villas, the building clearly detaches aesthetically from the Swiss-French architect’s previous works to introduce a more organic and massive style, characterized by the wide use of raw concrete (Béton Brut in French), that would eventually give birth to the so-called Brutalist architectural style and would anticipate some of Le Corbusier’s later works, such as the Saint Marie de La Tourette convent, the Notre Dame du Haut chapel – both in France -, and the series of buildings the architect designed in Chandigarh, northern India.

Aerial view from east, photo Denis Esakov (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) via Flickr.

Architecture

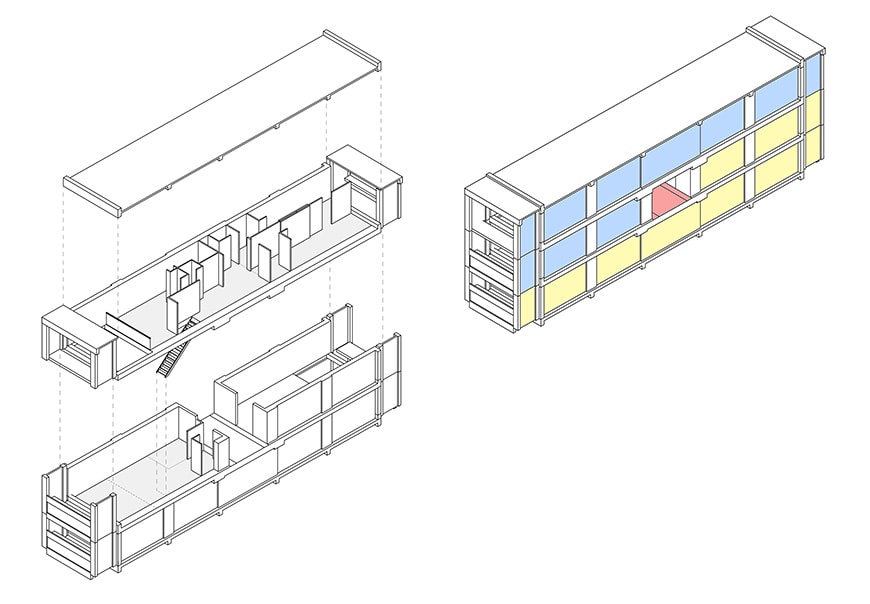

Le Corbusier’s idea was to create a “vertical garden-town”, an enormous 18-story building comprising 337 apartments of 8 different types (named from A to H) in 23 variants. Based on a 15.5-sqm / 167-sqft modular unit and with a gross floor area ranging from 15.5 sqm (one module) to 203 sqm / 2,185 sqft, the apartments can accommodate from 1 to 10 people; the most frequent type is the E one, a two-level apartment for 4 people with a floor area of 98 square meters / 1,055 square feet. Each apartment was conceived as a “machine for living” (machine-à-habiter) equipped with then-state-of-the-art technical facilities “to free women from household chores” (libérer la femme des contraintes domestiques), whose dimensions were based on Le Corbusier’s Modulor anthropometric scale.

On every floor, a 120-meter-long corridor gives access to the apartments and can also be used by the residents as a socializing/gathering space.

Le Corbusier regarded the Unité d’Habitation as the home of a large community of people rather than a simple residential building, therefore he designed various communal facilities for it, including gardens, shops, a restaurant, a library, a medical office, a pharmacy, a kindergarten, and a roof terrace with playgrounds, a swimming pool, and a small open-air theater.

The way the two-level flats stack on one another is very ingenious; one level of each residential unit occupies the entire building section while the other level occupies slightly less than a half-section, and the remaining space accommodates a communal corridor.

Flats on the left and right sides are different in all corridors. For example, in those on one side, people enter at the living room level and then go up to the sleeping area by an internal stair while, in the units on the opposite side, people enter at the dining room level and then go down to a lower level which houses the living room and all bedrooms.

This way, Le Corbusier was able to create modular flats of various types keeping the same structural module throughout the building and reducing the number of corridors.

The price to pay was rather tight internal spaces, at least for the current standards, and, sometimes, a slightly unwieldy internal distribution.

This layout is a variation of the appartement traversant, an apartment type quite common in France and Switzerland.

Close-up view of the east facade; photo Wojtek Gurak (CC BY-NC 2.0) via Flickr.

Axonometric drawing of an “E-type” two-level apartment; image by Alberto Contreras González (CC BY-SA 4.0) via Wikimedia Commons. The Unité d’Habitation in Marseille contains 8 types of apartments in 23 variants, all based on a 15.5-sqm module, that can accommodate from 1 to 10 people.

Plans and cross-section of typical two-level apartments. 1 – main corridor, 2 – entrance, 3 – kitchen, 4 – living room and lunchroom, 5 – lunchroom, 6 – double bedroom, 7 – single bedroom, 8 – balcony, 9 – void, 10 – double bedroom, 11 – living room, 12 – built-in wardrobe, 13 – bathroom, 14 – shower. Image by Inexhibit.

The building was raised on massive concrete pillars to leave the ground floor as free and open as possible; photo by Artur Salisz (CC BY-NC 2.0) via Flickr.

Two views of the roof terrace, photos by Guzmán Lozano (CC BY 2.0) via Flickr, and Michel Bonvin courtesy of The École Cantonale d’art de Lausanne (https://ecal.ch/fr/feed/events/1346/ecal-appartement-50-cite-radieuse/)

Reception

At the time of its construction, the Unité d’Habitation received a mixed reception; on the one hand, it was praised for its forward-looking design and architectural inventiveness, on the other hand, it was judged crude and alienating, mainly due to its enormous size (the nickname La Maison du Fada, meaning “The Madman’s house” in the local dialect, was coined by Le Corbusier’s detractors to make fun of the building by affirming that everyone living in it would be driven mad). Afterward, many considered it the prototype of an entire generation of ghetto-like public housing complexes characterized by low-quality living standards and poor architectural features. In my opinion, this harsh judgment is largely incorrect. The Unité in Marseille proved a pretty successful design indeed.

As envisaged by Le Corbusier, its inhabitants started forming a community immediately after the building was completed and populated in 1952; in 1953, they also founded a popular association of residents, which still exists today. At present, most of the residents declare themselves happy with the apartments and the building’s communal facilities and, despite its being built on a budget over seventy years ago in a rather peripheral area, the Unité is still quite popular among the Marseillais and the average price per square meter price of apartments exceeds €4,000 ($4,600).

Visiting the Unité d’Habitation

The Unité d’Habitation Marseille is located in the Sainte-Anne neighborhood in the city’s 8th arrondissement, it can be reached through the M1 and M2 rapid transit lines, stop “Castellane”, or by the B1 bus, stop “Le Corbusier”.

Though the building is permanently inhabited, some parts are open to the public. Visits are managed by the Association des Habitants de l’UH Le Corbusier Marseille and give access to various communal parts – including the lobby, the corridors on the 3rd and 4th levels with several shops opening onto them, the library, the winter garden, and the roof terrace – and two apartments, one of which features the original furniture designed by le Corbusier while the other accommodates changing exhibitions of art and design. The building also contains the MAMO contemporary art gallery on the roof terrace level, a hotel, and the restaurant “Le Ventre de l’Architecte”.

A communal staircase and a view of a communal corridor; photo Wojtek Gurak (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Unité d’Habitation Marseille, interior views of one of the apartments open to the public during the exhibition “ECAL Appartement 50”, 2015; photos Michel Bonvin courtesy of The École cantonale d’art de Lausanne.

The south facade; photo Wojtek Gurak (CC BY-NC 2.0) via Flickr.

How our readers rate this museum (you can vote)

copyright Inexhibit 2025 - ISSN: 2283-5474

(5 votes, average: 3.60 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 3.60 out of 5)